Hamlet Coloring Pages Late Middle Ages Fashion Design

Costume design for Gianetta - The Gondoliers

Costume blueprint is the creation of clothing for the overall appearance of a graphic symbol or performer. Costume may refer to the manner of dress item to a nation, a class, or a period. In many cases, it may contribute to the fullness of the artistic, visual world which is unique to a item theatrical or cinematic production. The most basic designs are produced to announce status, provide protection or modesty, or provide visual involvement to a character.[1] Costumes may be for a theater, cinema, or musical performance simply may not be limited to such. Costume design should not exist confused with costume coordination which simply involves altering existing clothing, although both create stage apparel.

Iv types of costumes are used in theatrical design: historical, fantastical, trip the light fantastic, and modern.[2]

History [edit]

Village festivals and processions in honor of Dionysus (See too: Dionysia) amidst the aboriginal Greeks, are believed to be the origin of theatre, and therefore theatre costume. The sculpture and vase paintings provide the clearest evidence of this costume.[1] Because of their ritualized way of theatre many masks were used giving each character a specific await and they varied depending if they were used for comedic or dramatic purposes. Some masks were constructed with a cheerful likewise as a serious side on the same confront in an attempt to point a change in emotion without a change of mask.[3] The same is true for the Romans, who continued the mask tradition, which made the doubling of roles easier.

During the tardily Middle Ages in Europe, dramatic enactments of Bible stories were prevalent, therefore actual Christian vestments, stylized from traditional Byzantine courtroom dress, were worn every bit costumes to keep the performances as realistic equally possible.[1] Stereotypical characterization was key when clothing performers for this style of theatre. In most instances actors had to supply their own costumes when playing a character institute in daily life.[4]

Afterwards, in Elizabethan performance during the 1500-1600s in England, costume became the almost important visual element. Garments were very expensive because only the finest fabrics were used. The majority of characters were clothed in Elizabethan fashion, otherwise the costumes could be divided into five categories; "Ancient", which was out of mode clothing used to represent some other menstruum; "Antique", older additions to gimmicky clothing to distinguish classical characters; Dreamlike, "fanciful" garments for supernatural or allegorical characters; "Traditional" wear which represented only a few specific people, such as Robin Hood, or "National or Racial" costumes that were intended to gear up apart a specific grouping of people but did not tend to be historically authentic.[5]

"Usually, stylish garments were used in both comedy and tragedy until 1727, when Adrienne Lecouvreur adopted the much more elaborate and formal court clothes for tragedy. Her practice soon became standard for all tragic heroines" [six] Major actors began to compete with one another as to who would have the most lavish stage dress. This practice continued until around the 1750s when costumes became relevant to the character once more. Art began to copy life and realistic characteristics were favored especially during the 19th century. For instance, Georg the 2d, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen took personal interest in the theatre and began managing troupes. He advocated for actuality and accurateness of the script and fourth dimension period, therefore he refused to let actors tamper with their own costumes. He also made sure the materials were authentic and specific, using existent chain mail, armor, swords, etc. No cheap substitutes would exist allowed.[vii]

In August 1823, in an upshot of The Album, James Planché published an article saying that more than attention should be paid to the time menses of Shakespeare'southward plays, peculiarly when it comes to costumes. In the aforementioned year, a coincidental conversation led to one of Planché's more lasting furnishings on British theatre. He observed to Charles Kemble, the manager of Covent Garden, that "while a thousand pounds were frequently lavished upon a Christmas pantomime or an Easter spectacle, the plays of Shakespeare were put upon the stage with makeshift scenery, and, at the best, a new wearing apparel or two for the primary characters."[viii] [9] Kemble "saw the possible advantage of correct appliances catching the gustatory modality of the town" and agreed to requite Planché control of the costuming for the upcoming product of King John, if he would carry out the research, blueprint the costumes and superintend the production.[10] Planché had little experience in this expanse and sought the help of antiquaries such as Francis Douce and Sir Samuel Meyrick. The enquiry involved sparked Planché's latent antiquarian interests; these came to occupy an increasing corporeality of his time after in life.[11]

Despite the actors' reservations, King John was a success and led to a number of similarly-costumed Shakespeare productions by Kemble and Planché (Henry Iv, Function I, As You Similar It, Othello, Cymbeline, Julius Caesar).[11] The designs and renderings of King John, Henry Four, Every bit You Like It, Othello, Hamlet and Merchant of Venice were published, though there is no evidence that Hamlet and Merchant of Venice were ever produced with Planché'southward historically authentic costume designs. Planché as well wrote a number of plays or adaptations which were staged with historically accurate costumes (Cortez, The Woman Never Vext, The Merchant's Hymeneals, Charles XII, The Partisans, The Brigand Chief, and Hofer).[12] After 1830, although he still used period costume, he no longer claimed historical accuracy for his work in plays. His work in King John had brought about a "revolution in nineteenth-century stage practice"[12] which lasted for nigh a century.[thirteen]

In 1923 the starting time of a series of innovative modernistic dress productions of Shakespeare plays, Cymbeline, directed by H. K. Ayliff, opened at Barry Jackson'southward Birmingham Repertory Theatre in England.[xiv]

Historical costumes of Le Cateau Cambrésis, France

Costumes in Chinese theatre are very important, especially in Beijing Opera. They are unremarkably heavily patterned and loud in color. The standard items consist of at to the lowest degree 300 pieces and describe the actors grapheme type, age and social status through ornament, design, color and accessories. "Color is always used symbolically: red for loyalty and high position, yellow for royalty, and dark crimson for barbarians or military advisors."[fifteen] Symbolic significance is also plant in the designs used for emblems. For case, the tiger stands for power and masculine force. A majority of the clothing, regardless of rank, is fabricated out of rich and luxurious materials. Makeup is also used symbolically and very important to the overall expect.

In Japanese Noh drama masks are always used and the prominent aspect of the costume. They are made of woods and usually used for generations. There are five basic types; male person, female, aged, deities and monsters, all with many variations.[sixteen] The masks are changed ofttimes throughout the play. In Kabuki, another form of Japanese theatre, actors do non clothing masks simply rely heavily on makeup for the overall expect. Features are exaggerated or removed and for some of the athletic roles musculature is outlined in a specific blueprint. Traditional costumes are used for each role, based upon historical garments that are altered for dramatic effect. "Some costumes weigh every bit much equally 50 pounds, and stage attendants assist the actors in keeping them properly bundled while on phase" [17]

Design process [edit]

The costume design procedure involves many steps and though they differ from genre to genre a bones method is commonly used.

1. Assay:

The starting time step is an analysis of the script, musical composition, choreography, etc. Costume Parameters for the show are established and a rough costume plot is created. A costume plot outlines which grapheme is in which scene, when the actors change, and what costumes are mentioned in the script.

2. Design collaboration: An important phase in the process where all of the designers meet with the director. There must be a clear agreement of where the show is headed. The designers go on the aforementioned page with the director in terms of themes for the show and what message they want the audience to go from the show.

3. Costume research: Once the manager and designers are on the same page, the next step is for the Costume designer to assemble research. Costume designers usually begin with world of the play research where they notice research to found the globe where the play takes place. This helps the designers plant the rules of the world and and then in turn understand the characters amend. The designer will then go into broad research nigh each graphic symbol to try to establish their personalities though their costume.

A woman creating in a costume workshop in Prague theater.

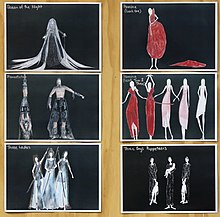

4. Preliminary sketching and color layout: Once enough information is obtained, Costume designers begin by creating preliminary sketches. commencement with very quick rough sketches the designer tin can go a basic idea for how the show will look put together and if the rules of the world are being maintained. The Costume designer will then go into more than detailed sketches and volition figure out the specific costumes and colors for the character. Sketches help see the bear witness as a whole without them having to spend too much time on them.

five. Final sketches: Once the Costume Designer and the Director hold on the costumes and the ideas are fully flushed out, the designer will create last sketches. These are called rendering and are normally painted with watercolors or acrylic paints. These final sketches testify what the designer wants the character to wait similar and the colors of the costume.

[18]

Product process [edit]

Example of draping muslin fabric onto a dress class

Once the prove is designed, it is necessary to programme where the items volition be sourced. At that place are iv options. Garments can be:

- Pulled, which refers to searching through a costume shops stock

- Rented

- Shopped

- Constructed, or also known equally fabricated to order.

There are two means a garment can brainstorm to be constructed; either pattern drafted or draped, and many times both methods will be used together. Pattern drafting begins by using a set of basic design blocks developed from the actor's measurements. They are drawn out on newspaper first, and so transferred to fabric, and sewn together to test fit.[19]

Draping involves manipulating a slice of material on a wearing apparel form or mannequin that accept measurements closely related to the actors. It is a process that takes a flat slice of cloth and shapes it to conform the textile to a three-dimensional body by cutting and pinning.

Once constructed, notwithstanding, the costume has not finished "working." A most important aspect of costumes is the means they touch on actors' performances and part inside their settings. The very best costume designers build their original ideas after assessing the visual and spatial weather condition of the costumes.[xx]

Come across also [edit]

- Costume designer

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Eubank, Tortora, Keith, Phyllis G. (2005). Survey of Celebrated Costume. New York: Fairchild Publications. p. ane.

- ^ Grimball and Wells, Elizabeth B. and Rhea (1925). Costuming a Play: Inter-Theatre Arts Handbook. The Century Co. p. 6. ASIN B0000D5ITV.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar K., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. USA: Pearson Instruction Inc. p. 53. ISBN0-205-47360-one.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar K., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. U.s.: Pearson Education Inc. p. 96. ISBN0-205-47360-1.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar 1000., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. USA: Pearson Instruction Inc. p. 125. ISBN0-205-47360-ane.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar M., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. Usa: Pearson Didactics Inc. p. 254. ISBN0-205-47360-1.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar Chiliad., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. USA: Pearson Instruction Inc. p. 358. ISBN0-205-47360-1.

- ^ Obituary, The New York Times, xv June 1880, p3

- ^ Reinhardt, The Costume Designs of James Robinson Planché, argues that a letter published in The Anthology, August 1823, pp298–304, signed simply 'P', which called for more attention to exist paid to the costuming of Shakespeare'south plays, and proposed a wardrobe organisation whereby all locations and periods could be accommodated, was in fact written by Planché.

- ^ Obituary, The New York Times. The playbill for Male monarch John states that if the play meets with "beatitude and patronage" more of Shakespeare'south plays will be performed "Dressed in the same splendid, novel, and interesting style".

- ^ a b Reinhardt, The Costume Designs of James Robinson Planché, p526–seven

- ^ a b Roy, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Granville-Barker, Exit Planché—Enter Gilbert, p. 107

- ^ Morris, Sylvia (2012-01-13). "Innovating in Birmingham: Barry Jackson and modern dress Shakespeare". The Shakespeare blog . Retrieved 2012-03-21 .

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar G., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. Usa: Pearson Pedagogy Inc. p. 201. ISBN0-205-47360-1.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar Chiliad., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. United states of america: Pearson Education Inc. p. 206. ISBN0-205-47360-ane.

- ^ Brockett, Hildy, Oscar M., Franklin J. (2007). History of the Theatre. United states of america: Pearson Education Inc. p. 211. ISBN0-205-47360-1.

- ^ Covey, Ingham, Liz, Rosemary (1992). The Costume Designer's Handbook. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. pp. fifteen–100.

- ^ Covey, Ingham, Liz, Rosemary (2003). The Costume Technician's Handbook. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. p. 98.

- ^ Lugli, Emanuele. "Costume as Appearance: A Study in the Modalities of Existence of Film Costumes".

External links [edit]

- "Costume Designs and Designers Collections" held in the "Performing Arts Drove", at Arts Centre Melbourne.

- "The National Costumers Association" Nationwide Non-Turn a profit organization for costume designers and costumers.

- "The Stagecraft Wiki" A Wiki defended to technical theater arts. Part of Stagecraft.com

- IDD: Costume & Theatrical International Costume & Theatrical Pattern Directory

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections - Fashion Plates Costumes

- Costumes of All Nations 104 plates of costumes

- Williams College Theatre Department a database of costumes with VR movies and the original sketches

- "Stagelink" Theatrical costume, makeup and wig resources

- Theatre Costume and Set Design Archive at the University of Bristol Theatre Drove, Academy of Bristol

- The 50 films that changed men's style

- "British Order of Theatre Designers"

- Costume Design training in Auckland NZ at Unitec Performing and Screen Arts

- Costume Designs of Early on Films on the European Film Gateway

0 Response to "Hamlet Coloring Pages Late Middle Ages Fashion Design"

Post a Comment